This has been a terrific day. No rain, just pleasant sunshine, a breeze and an occasional cloud. Perfect sightseeing weather.

The bus to Mikines, the modern village, and Mycenae, the ancient site, goes via Argos, which is what we would call the county town, and a very straightforward place, not at all touristy. If I needed to get my photocopier fixed, I could get that done in Argos (not that I have a photocopier, but still...). I did see signs for the archaeological sites there, which is encouraging; there's also a splendid castle on the Larisa hill and I spotted a WW2 pillbox beside the railway line.

Then the bus route runs out of the town and across the Argive Plain, through miles of orange orchards, and finally up into Mikines, and along a last mile or so of winding tree-lined road towards the citadel of Mycenae itself. You can see it from the road and it is dramatic even then; ringed with massive walls and dominating a ridge between two conical hills, it looks as though it's enthroned there. The place has a real quality of drama, which a neat fence with an entrance gate and ticket booth cannot detract from at all.

It isn't just the terrible, bloody family history of the myths based here; it's the place itself. This is the architecture of power if ever I saw it. The walls are tremendous, and the Lion Gate is every bit as impressive as its reputation suggests. Arriving is almost a piece of theatre; the gateway is concealed between two outworks, great bastions of cyclopean masonry; you toil up a steep slope and come in between the bastions, completely dwarfed by them, and then these two grey stone lionesses loom above you, and the gate is square and wide and carries them high.

Then as you come in, there would have been double doors, and guards, and the next thing you saw would have been the stone parapet round a great circle of ancestral tombs, and then a huge paved entrance ramp ahead, leading up between fine stone buildings...

Whoever first conceived and built this place wanted to impress people, of that I am sure. I imagine someone who perhaps had travelled, seen Egypt or the Hittite cities, come home and made good, and who decided that his city was going to be like that, too; that it was going to be not just defensible but a statement.

Back in 1989, I had got talking on the bus to Mycenae to a nurse from Brixton called Ruth, and we ended up touring the site together. We nearly broke our necks a couple of times; the whole place was a bit less tidy then, and we just scrambled about unchecked. For example, there's an amazing underground cistern, which is open to visitors.

Today I found a rope across the ancient rock-cut stairs after a while, stopping one from going all the way down. In 1989 Ruth and I duly set off down these same steps into the dark, and there was no rope; we turned the corner at the bottom of the first flight and were instantly in total blackness. I produced a box of matches with a proud flourish that neither of us could see, and struck one; and it made not a blind bit of difference. We were still in pitch darkness, laughing our heads off. We turned around carefully and picked our way out. Later I discovered we'd got alarmingly close to falling off a steep drop; the tunnel ends in a shaft something like 18 feet deep.

The postern gate is closed off with a grille now, too, but the north gate is still open, and they've fitted a pair of wooden doors, so that you can see how it was done.

Three of the "minor" tholos tombs have been made safe (more memories of Ruth and I scrabbling about taking silly risks; we almost fell into one of these, poking about carelessly). They are extraordinary structures.

And Grave Circle B, the slightly later set of ancestral tombs just outside the walls, has been re-dug and tidied up a bit. One of the tombs has been restored, to show how they would have looked; a low tumulus ringed with white stones, and a carved stone slab on top. The carved marker is a reproduction but the effect is no less striking for that.

At Grave Circle A, the older one, inside the walls, Heinrich Schliemann, the discoverer of Troy, excavated an incredible collection of treasure. Mycenae is always called "rich in gold" in Homer, and his discoveries proved the accuracy of that epithet. Schliemann wasn't much of an archaeologist by today's standards, though at least he was better than Lord Elgin, just ripping stuff down to take the pretties (and Schliemann's finds did end up in Athens, too). But he was certainly a visionary. I don't know how easy it would be now for a wealthy amateur enthusiast to start excavating a place he suspected was worth digging, just like that; probably totally impossible. Which is a good thing, of course; and yet - if the rules of today had applied in the 1860s, Troy might never have been excavated at all (Mycenae probably would have been eventually, since people did at least know it was there).

All the gold and silver and bronze Schliemann found had been buried with a group of people who he assumed were Agamemnon and his party, murdered on their return from Troy. Today I overheard one of the guides telling her group that DNA testing a few years ago by the University of Manchester has established that two of the women buried there were very closely related, probably sisters, and were also related to one of the men. It's tantalising wondering who they were.

I mentioned the legends earlier; if you already know the stories, look away now. If not, brace yourself, because if you thought the story of Hyrnetho was a bit violent, you ain't heard nothing yet. The mythology of Mycenae is blood-boltered and grim in the extreme, and the violence goes on for generations.

Mycenae was traditionally founded by Perseus, the killer of the Gorgon Medusa and rescuer of Andromeda from the sea-monster her parents had sacrificed her to. He had accidentally killed his grandfather Akrisios, the king of Argos, with a discus throw. He then inherited Argos, but felt unable to assume the throne in the circumstances, and swapped it for some land a few miles away where he built a new town overlooking the Argive Plain; Mycenae. His son Sthenelos ruled next, and then his grandson Eurystheus. But Eurystheus died in the same battle as his only son, and for some reason the city then passed not to the children of Eurystheus' cousin Herakles (yes, that Herakles), but to a young man named Pelops who had a, shall we say, less than trouble-free background.

Pelops' father Tantalos had wanted to test the Gods, so he had killed Pelops when he was just a boy and jointed him up, and served him to them as a casserole. Demeter, grieving over the rape and abduction of her daughter Persephone, actually ate a bit before she realised. Tantalos was punished and Pelops was restored to life, with an ivory replacement for the bitten-off chunk of his shoulder. Not a good start in life. He grew up anyway, ivory shoulder and all, went off to seek his fortune, and ended up competing in a chariot race with King Oinomaos of Elis.

Oinomaos, like so many kings in folk tales, had just one child, a daughter, Hippodameia, and had promised her hand in marriage to whoever could beat him in a race. But, again like so many kings, at least in Greek mythology, he'd also been given a prophecy that whoever married Hippodameia would kill him. So in the course of these chariot races he murdered the suitors, by spearing them from behind when they overtook him.

Pelops wasn't going to play fair in the face of that, so he bribed the king's charioteer Myrtilos to take out the bronze axle pins of the royal chariot and replace them with wax. Once the chariot was moving, friction melted the wax, the wheels came off and it crashed; Myrtilos, who obviously knew what was happening, was thrown clear, but the king fell and was killed. Pelops married Hippodameia, and murdered Myrtilos to stop him telling.

The dying Myrtilos cursed Pelops and all his descendants.

Jump forward a generation, and Pelops and Hippodameia's three sons were Atreus, Thyestes and Chrysippos. The elder two murdered Chrysippos because he was their father's favourite. Atreus inherited the throne and Thyestes promptly had an affair with his wife. Atreus retaliated by killing two of Thyestes three children and cooking them in a pie; he served it to Thyestes who thus ate his own flesh and blood. Thyestes then cursed his brother, doubling the amount of curse-burden on the family. He went on to raise his youngest son, Aegisthos, to avenge his brothers at any cost.

Atreus had two sons, Agamemnon and Menelaos; they married the sisters Klytemnestra and Helen. Helen ran away to Troy with Paris and the brothers gathered their great expedition to go to war against the Trojans. At the last minute they were delayed by adverse winds, and Agamemnon was told to sacrifice his daughter Iphigeneia to propitiate the Gods; he did so, the wind changed, and off they all sailed. Ten years at Troy, and then a couple more sailing home; a long absence in which the embittered family left at home could plot and plan. Klytemnestra had sworn to avenge her daughter. She began an affair with Thyestes' son Aegisthos, and when Agamemnon finally got home they murdered him in his bath. Ten years or so later, they were in their turn murdered by Klytemnestra and Agamemnon's son Orestes, avenging his father. He was pursued by the Furies, the goddesses of retribution (matricide being one of the ultimate crimes, exceptional even in this murderous family); he went insane and wandered for a while as a wild madman, before finally being tried, acquitted, and cleansed of blood-guilt in Athens. The Furies then took up residence there (in that cave under the Areopagos) where they were honoured as the Eumenides, the Kindly Ones, bringers of justice.

I told you it was bloody.

When you consider the possibility that myths often reflect something real - if not actual specific events and people, then at least generalised folk memories of "what things were like then" - then these stories imply a horrific amount of murder and human sacrifice went on in the royal families of Bronze Age Greece. It makes the Wars of the Roses look positively tame.

In spring, Mycenae is covered, most appropriately, with blood-red poppies; now, in autumn, it's baked dry, but there are cyclamen peeping through here and there, and other wildflowers just starting to grow and bloom. Lizards run among the stones and there are masses of nuthatches singing and doing territorial displays everywhere. I even met a snail.

I also met one bit of less benign wildlife; an enormous hornet dragging a very large dead spider along the ground. I wanted to take a photograph, but the hornet took exception and chased me down the entryway of a tholos tomb. I didn't want to steal its spider, just play bug-paparazzi, but I wasn't going to make another try and risk getting a hornet sting. So no photos, I'm afraid. Some of you may be glad of that, of course, large spiders not being everyone's cup of tea, after all...

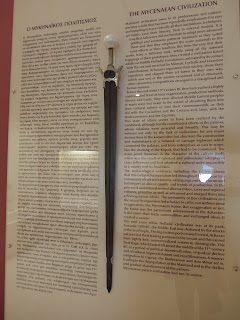

There's a small site museum nowadays, with yet another very well-thought-out display, with timelines and some excellent exhibits. Most of the "big" treasures are in the National Museum in Athens, but there's plenty to see here, too. My camera battery ran out in the second room, though. So only a few pictures of pots this time!

I did a couple of quick sketches; the entrance to the underground cistern, with its corbelled roof, and an overview of the site as a whole, from the bus stop. The latter is unfinished because the bus arrived.

Incidentally, if anyone reading this has a copy of Pausanias and has looked up Nafplio (Nauplion in his day) and thought "Why's she gone there, then?" after seeing how little he says about it; well, this is why. It's a great base for the area, and a base also for the Argolid regional bus service; if you're travelling by public transport, Nafplio is easily the best place to start from to visit Mycenae.

I have seriously tired legs now, though.

The bus to Mikines, the modern village, and Mycenae, the ancient site, goes via Argos, which is what we would call the county town, and a very straightforward place, not at all touristy. If I needed to get my photocopier fixed, I could get that done in Argos (not that I have a photocopier, but still...). I did see signs for the archaeological sites there, which is encouraging; there's also a splendid castle on the Larisa hill and I spotted a WW2 pillbox beside the railway line.

Then the bus route runs out of the town and across the Argive Plain, through miles of orange orchards, and finally up into Mikines, and along a last mile or so of winding tree-lined road towards the citadel of Mycenae itself. You can see it from the road and it is dramatic even then; ringed with massive walls and dominating a ridge between two conical hills, it looks as though it's enthroned there. The place has a real quality of drama, which a neat fence with an entrance gate and ticket booth cannot detract from at all.

It isn't just the terrible, bloody family history of the myths based here; it's the place itself. This is the architecture of power if ever I saw it. The walls are tremendous, and the Lion Gate is every bit as impressive as its reputation suggests. Arriving is almost a piece of theatre; the gateway is concealed between two outworks, great bastions of cyclopean masonry; you toil up a steep slope and come in between the bastions, completely dwarfed by them, and then these two grey stone lionesses loom above you, and the gate is square and wide and carries them high.

Then as you come in, there would have been double doors, and guards, and the next thing you saw would have been the stone parapet round a great circle of ancestral tombs, and then a huge paved entrance ramp ahead, leading up between fine stone buildings...

Back in 1989, I had got talking on the bus to Mycenae to a nurse from Brixton called Ruth, and we ended up touring the site together. We nearly broke our necks a couple of times; the whole place was a bit less tidy then, and we just scrambled about unchecked. For example, there's an amazing underground cistern, which is open to visitors.

Today I found a rope across the ancient rock-cut stairs after a while, stopping one from going all the way down. In 1989 Ruth and I duly set off down these same steps into the dark, and there was no rope; we turned the corner at the bottom of the first flight and were instantly in total blackness. I produced a box of matches with a proud flourish that neither of us could see, and struck one; and it made not a blind bit of difference. We were still in pitch darkness, laughing our heads off. We turned around carefully and picked our way out. Later I discovered we'd got alarmingly close to falling off a steep drop; the tunnel ends in a shaft something like 18 feet deep.

The postern gate is closed off with a grille now, too, but the north gate is still open, and they've fitted a pair of wooden doors, so that you can see how it was done.

Three of the "minor" tholos tombs have been made safe (more memories of Ruth and I scrabbling about taking silly risks; we almost fell into one of these, poking about carelessly). They are extraordinary structures.

And Grave Circle B, the slightly later set of ancestral tombs just outside the walls, has been re-dug and tidied up a bit. One of the tombs has been restored, to show how they would have looked; a low tumulus ringed with white stones, and a carved stone slab on top. The carved marker is a reproduction but the effect is no less striking for that.

At Grave Circle A, the older one, inside the walls, Heinrich Schliemann, the discoverer of Troy, excavated an incredible collection of treasure. Mycenae is always called "rich in gold" in Homer, and his discoveries proved the accuracy of that epithet. Schliemann wasn't much of an archaeologist by today's standards, though at least he was better than Lord Elgin, just ripping stuff down to take the pretties (and Schliemann's finds did end up in Athens, too). But he was certainly a visionary. I don't know how easy it would be now for a wealthy amateur enthusiast to start excavating a place he suspected was worth digging, just like that; probably totally impossible. Which is a good thing, of course; and yet - if the rules of today had applied in the 1860s, Troy might never have been excavated at all (Mycenae probably would have been eventually, since people did at least know it was there).

All the gold and silver and bronze Schliemann found had been buried with a group of people who he assumed were Agamemnon and his party, murdered on their return from Troy. Today I overheard one of the guides telling her group that DNA testing a few years ago by the University of Manchester has established that two of the women buried there were very closely related, probably sisters, and were also related to one of the men. It's tantalising wondering who they were.

I mentioned the legends earlier; if you already know the stories, look away now. If not, brace yourself, because if you thought the story of Hyrnetho was a bit violent, you ain't heard nothing yet. The mythology of Mycenae is blood-boltered and grim in the extreme, and the violence goes on for generations.

Mycenae was traditionally founded by Perseus, the killer of the Gorgon Medusa and rescuer of Andromeda from the sea-monster her parents had sacrificed her to. He had accidentally killed his grandfather Akrisios, the king of Argos, with a discus throw. He then inherited Argos, but felt unable to assume the throne in the circumstances, and swapped it for some land a few miles away where he built a new town overlooking the Argive Plain; Mycenae. His son Sthenelos ruled next, and then his grandson Eurystheus. But Eurystheus died in the same battle as his only son, and for some reason the city then passed not to the children of Eurystheus' cousin Herakles (yes, that Herakles), but to a young man named Pelops who had a, shall we say, less than trouble-free background.

Pelops' father Tantalos had wanted to test the Gods, so he had killed Pelops when he was just a boy and jointed him up, and served him to them as a casserole. Demeter, grieving over the rape and abduction of her daughter Persephone, actually ate a bit before she realised. Tantalos was punished and Pelops was restored to life, with an ivory replacement for the bitten-off chunk of his shoulder. Not a good start in life. He grew up anyway, ivory shoulder and all, went off to seek his fortune, and ended up competing in a chariot race with King Oinomaos of Elis.

Oinomaos, like so many kings in folk tales, had just one child, a daughter, Hippodameia, and had promised her hand in marriage to whoever could beat him in a race. But, again like so many kings, at least in Greek mythology, he'd also been given a prophecy that whoever married Hippodameia would kill him. So in the course of these chariot races he murdered the suitors, by spearing them from behind when they overtook him.

Pelops wasn't going to play fair in the face of that, so he bribed the king's charioteer Myrtilos to take out the bronze axle pins of the royal chariot and replace them with wax. Once the chariot was moving, friction melted the wax, the wheels came off and it crashed; Myrtilos, who obviously knew what was happening, was thrown clear, but the king fell and was killed. Pelops married Hippodameia, and murdered Myrtilos to stop him telling.

The dying Myrtilos cursed Pelops and all his descendants.

Jump forward a generation, and Pelops and Hippodameia's three sons were Atreus, Thyestes and Chrysippos. The elder two murdered Chrysippos because he was their father's favourite. Atreus inherited the throne and Thyestes promptly had an affair with his wife. Atreus retaliated by killing two of Thyestes three children and cooking them in a pie; he served it to Thyestes who thus ate his own flesh and blood. Thyestes then cursed his brother, doubling the amount of curse-burden on the family. He went on to raise his youngest son, Aegisthos, to avenge his brothers at any cost.

Atreus had two sons, Agamemnon and Menelaos; they married the sisters Klytemnestra and Helen. Helen ran away to Troy with Paris and the brothers gathered their great expedition to go to war against the Trojans. At the last minute they were delayed by adverse winds, and Agamemnon was told to sacrifice his daughter Iphigeneia to propitiate the Gods; he did so, the wind changed, and off they all sailed. Ten years at Troy, and then a couple more sailing home; a long absence in which the embittered family left at home could plot and plan. Klytemnestra had sworn to avenge her daughter. She began an affair with Thyestes' son Aegisthos, and when Agamemnon finally got home they murdered him in his bath. Ten years or so later, they were in their turn murdered by Klytemnestra and Agamemnon's son Orestes, avenging his father. He was pursued by the Furies, the goddesses of retribution (matricide being one of the ultimate crimes, exceptional even in this murderous family); he went insane and wandered for a while as a wild madman, before finally being tried, acquitted, and cleansed of blood-guilt in Athens. The Furies then took up residence there (in that cave under the Areopagos) where they were honoured as the Eumenides, the Kindly Ones, bringers of justice.

I told you it was bloody.

When you consider the possibility that myths often reflect something real - if not actual specific events and people, then at least generalised folk memories of "what things were like then" - then these stories imply a horrific amount of murder and human sacrifice went on in the royal families of Bronze Age Greece. It makes the Wars of the Roses look positively tame.

In spring, Mycenae is covered, most appropriately, with blood-red poppies; now, in autumn, it's baked dry, but there are cyclamen peeping through here and there, and other wildflowers just starting to grow and bloom. Lizards run among the stones and there are masses of nuthatches singing and doing territorial displays everywhere. I even met a snail.

I also met one bit of less benign wildlife; an enormous hornet dragging a very large dead spider along the ground. I wanted to take a photograph, but the hornet took exception and chased me down the entryway of a tholos tomb. I didn't want to steal its spider, just play bug-paparazzi, but I wasn't going to make another try and risk getting a hornet sting. So no photos, I'm afraid. Some of you may be glad of that, of course, large spiders not being everyone's cup of tea, after all...

There's a small site museum nowadays, with yet another very well-thought-out display, with timelines and some excellent exhibits. Most of the "big" treasures are in the National Museum in Athens, but there's plenty to see here, too. My camera battery ran out in the second room, though. So only a few pictures of pots this time!

I did a couple of quick sketches; the entrance to the underground cistern, with its corbelled roof, and an overview of the site as a whole, from the bus stop. The latter is unfinished because the bus arrived.

I have seriously tired legs now, though.

No comments:

Post a Comment